Interview: Yoshikatsu Fuji

Rabbits Abandon Their Children

An Interview with Yoshikatsu Fuji by Kristian Haggblom & James Bugg

Yoshikatsu Fuji's latest photobook Hiroshima Graph - Rabbits abandon their children is a beautiful handmade photobook that was the result of a long term research project and was made physical through a workshop with Yumi Goto and Reminders Photography Stronghold. In this interview with Dr. Kristian Haggblom and James Bugg, Fuji discusses the the background of this project, how it fits into a larger ongoing project on similar themes, and how it relates and differs to his successful 2014 book Red String.

James Bugg: Yoshikatsu, first congratulations on being awarded the 2017 Anamorphosis Prize for your remarkable photobook Hiroshima Graph - Rabbits abandon their children. The work, which culminates in a beautifully handmade photobook tackles incredibly dark aspects of Japan’s history with equal parts depth and poetic contemplation. Would you be able to give a little bit of background on this project and how it came about?

Yoshikatsu Fuji: Thank you. I hope that through this award more people can learn about what happened at Ōkunoshima, a small island located in the Inland Sea of Japan in the city of Takehara, Hiroshima Prefecture, also known as ‘Rabbit Island.’ In 1925, the Imperial Japanese Army Institute of Science and Technology initiated a secret program to develop chemical weapons, based on extensive research that showed that chemical weapons were being produced throughout the United States and Europe. The island was chosen for its isolation and because it was far enough from Tokyo and other large metropolitan areas in case of disaster. Under the jurisdiction of the Japanese military, the local fish preservation processor was converted into a toxic gas reactor. Residents and potential employees were not told what the plant was manufacturing and working conditions were harsh. Many inhabitants of the island subsequently suffered from toxic-exposure related illnesses.

With the end of the war, documents concerning the plant were burned and Allied Occupation Forces disposed of the gas either by dumping, burning, or burying it, and people were told to keep silent about the project. Several decades later, victims from the plant were given government aid for treatment. More recently, the story has become well-known and in 1988 the Ōkunoshima Poison Gas Museum was opened.

Most of the bomb victims, including my two grandmothers, are over 90-years-old now and I believe that is crucial that we listen to their stories while we still can. Three years ago, I moved from Tokyo back to Hiroshima for my photography career. Once settled, I felt it strange that people only talked from the perspective of atomic bomb victims, while staying mostly silent about the historic atrocities carried out by Japan against other countries. While thinking about this, I discovered the history of Ōkunoshima. Though in other areas of Japan and including even Hiroshima, there aren't many people who know about this island. It's difficult for anyone to talk about the sins they've committed in the past, but as a Hiroshima-born photographer, I wanted to do this in a way only I could. My ideal method of achieving this was through a handmade photobook.

Kristian Häggblom: You have mentioned that you are working on a greater project investigating nuclear and chemical legacies associated with war and Hiroshima Graph is a ‘chapter’ or part of a larger body of work you are researching and making. Can you please tell us more about this?

YF: When I was researching Ōkunoshima, I discovered that there are other islands around Hiroshima that were also ravaged by war and associated activities. These islands all contain dormant memories of the war and events at Hiroshima, and I would like to dig these memories up and plan to continue this theme moving forward.

JB: The island of Ōkunoshima, a current tourist destination, was the location of terrible events after the first World War. How did you go about documenting a tourist destination in a way that was reflective of the torment and pain of its past?

YF: My first priority was to hear directly from those who experienced these events. I had imagined that it would be remembered as a horrible tragedy, but I learnt that even through all the pain and suffering, the people still managed to find happiness and hope in their daily lives, and I resolved to record their stories in my book as accurately as possible.

"What can I do as a photographer? Exhibitions of this work are only temporary and may live on online, but the photobook will remain forever. That was my reason behind creating a photobook."

KH: How can we inform the younger generations of this terrible past, largely kept secret by the Japanese government, through photography? And through the medium of a photobook?

YF: In Hiroshima, people are being trained to pass down the accounts of what happened with the atomic bomb. However, in a lot of relatively unknown places like Ōkunoshima, if those originally involved are no longer with us, then there'll be no one left to tell the poignant stories. What can I do as a photographer? Exhibitions of this work are only temporary and may live on online, but the photobook will remain forever. That was my reason behind creating a photobook.

JB: In your publication rabbits become a linking thread and a metaphor throughout this work. Can you talk about how this creature became a reflection of some of the ideas and meanings you were trying to convey?

YF: The subtitle "Rabbits abandon their children" is a Japanese proverb that refers to irresponsible people. The Japanese government is not actively working to preserve this island, and there isn't enough social security for the former workers, so the rabbits are a metaphor for the Japanese government.

JB: This relates to Kristian’s question above… It would be easy to label Hiroshima Graph under the broad and somewhat simplistic term of ‘aftermath’ or ‘late’ photography. However, the work seems to go beyond this term and becomes something much more deeply reflective. Weaving between historical documents, found photos and your own documentation of place, Hiroshima Graph seems to acknowledge the distance between the work and the events in a way that is new and informative. How did you go about making work that was more than just documenting the trace of an event?

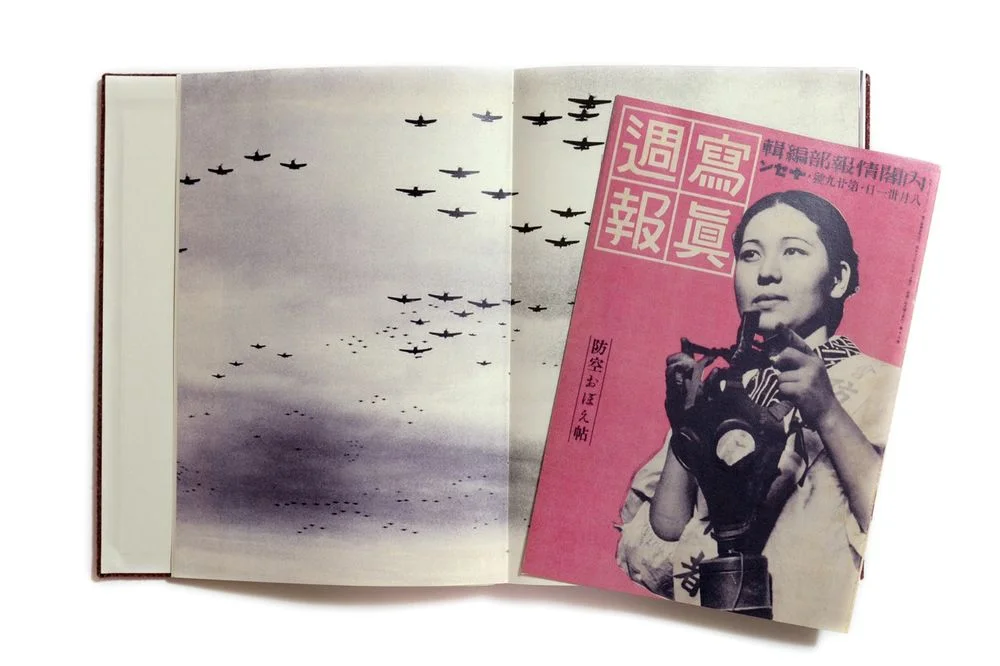

YF: I believe that I cannot depict the terrible events that took place on Ōkunoshima through my own photography alone. Archival images and text are an important element within the project and pertain to an examination of history because obviously we cannot go back to photograph the past. I chose images that would drive the story, and old photographs have a lot of power because of their age. In my selection, I had to take care to maintain a good balance between the archival images and my own photographs. It was also important to convey that the island is now a kind of tourist paradise.

JB: The handmade construction of the book adds to the well thought through and engaging nature of the work. Varied layouts and inserts within the book create a certain tactility to the work while also adding layers to the story. What were some of the ideas behind these design decisions and can you tell us a bit about the book as an object?

YF: I started with the modern peaceful imagery and designed it so the history gradually becomes clearer through the story and slow introduction of archival materials. I tried to structure it in a way that holds the reader's attention by repeating the cycle of tension and release. For example, there were four places where I put in little booklets containing archive photos to increase the feeling of tension, and then released this tension on the next page through more scenic photography. This is the narrative I was seeking to build up and down and keep the viewer engaged but also asking them to question the story and content.

KH: I visited Reminders Photography Stronghold recently and met some of the people involved. It was during Mayumi Suzuki’s great exhibition The Restoration Will. Can you tell us about working with Yumi Goto and RPS? Is this becoming a genre of Japanese photography? Many subjects and themes explored are deep and connected and the resulting books are complex and layered (physically and conceptually).

YF: On the surface, if you just pay attention to the way photobooks are produced through RPS workshops (which are presently dominating international photobook awards) it would be easy to assume that you just have to participate in order to produce something great, but that isn't entirely true. If the photographers involved don’t dedicate themselves tirelessly to working on a book – during and after workshops – the final photobook would be incomplete and not likely unappreciated.

Yumi Goto is very patient with artists who put hard work into their ideas and publishing. These photographers aren't afraid of change, but by the same token, there are a lot of participants who can't keep up with her difficult standards and don't manage to complete their photobooks.

Mayumi Suzuki's work is so good because unlike a lot of other disaster photographs, which show nothing but rubble, she uses her own unique method to turn them into a form of art. I think that RPS is the perfect environment because it's a gathering place for photographers like Mayumi who aren't afraid to put in effort, who can then work together to improve and produce engaging and important results.

JB: This work follows your 2014 book Red String which deals with history on a more personal level. How did you adjust from making work about your family to a much larger and extremely complex subject?

YF: I don't think these two books are all that different. While Red String is about the extremely personal issue of my parents' divorce, there are similar stories not just in Japan, but in other places like Korea and China as well. It is precisely because divorce is such a widespread issue that people in Europe were able to emphasize with my feelings expressed in the book. Even Hiroshima Graph started from the fact that I am personally a third-generation affected by the war and nuclear legacies.

JB & KH: What’s next?

YF: I'm going to keep working on the Hiroshima Graph project. It's scheduled for exhibition at RPS in August this year. Although it wasn’t mentioned in the photobook: why was poisonous gas being produced at Ōkunoshima? And what did they do with the gas made there? I want to include these details in the exhibition – all will be revealed…

Handmade photobook Hiroshima Graph by Yoshikatsu Fuji from Yoshikatsu Fuji on Vimeo.

In this interview with Dr. Kristian Haggblom, Obara discusses the aftermath of the release of his award winning book. He also lets us in on his new Chernobyl project, and further explores Asian war atrocities through his new projects.